Work together on a family tree project

If you're looking for a unique way to inspire your children's curiosity and interest in history, consider introducing them to genealogy. You can use your own family tree to:

- make history more relevant and meaningful to children

- strengthen their sense of identity

- help them to see where they fit in time and place in this world

Using your family tree to learn about the life and times of grandparents is a great example of "social history," which studies the experiences of ordinary people. Notice the word experiences - if you portray history in terms of experiences rather than facts, it can help personalize the study of history. This helps children to make sense of the world around them.

Jump to:

Consider your situation

For some students, the study of their own family tree might be difficult emotionally or logistically. In these situations, try the inclusionary suggestions here.

For adopted or long-term foster children who want to include both biological and adoptive/foster families, Adoption.com suggests these ideas:

- An entwined tree-two separate trees with trunks entwined then branching off to one side for the biological family and the other side for the adoptive family

- A roots and branches tree-a tree with roots labeled for biological family and branches labeled for adoptive family

- A mirror tree-similar to roots and branches, but a mirrored tree instead of roots at the bottom, giving two full trees to fill out for both families

Another idea is a "Circle of Care" instead of a tree - a spiral of individuals who care for and support the child.

Create learning hooks with genealogy

Genealogy offers an excellent approach because it makes history relevant, meaningful, and personal. In terms of psychological development, it leads to broader thinking about oneself and one's place in the world - and in time. When we have relevant and personal hooks, learning is more likely to stick.

"How am I connected to the past? Does this mean I am also connected to the future? What might that look like?"

Children might start by asking questions about their own family, writing about themselves, and making a family tree chart that starts with them. Over time, they learn to widen their focus to their community, state, and nation. With such a foundation in place, they can then expand to learning about other cultures and nations.

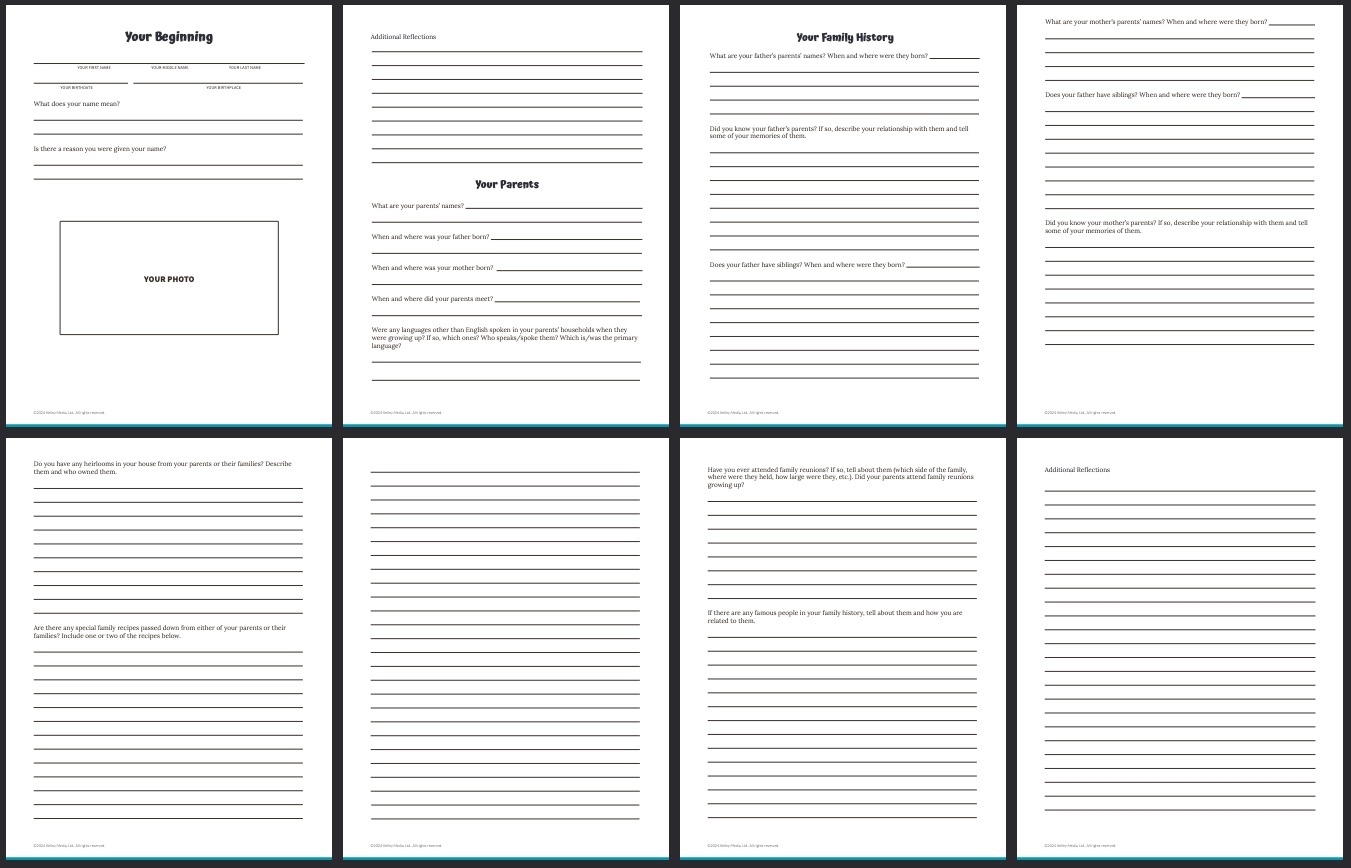

Get our Your Story printable

Our Your Story printable is a personal story workbook kids can use to start writing about themselves or interviewing parents or grandparents.

Spark curiosity with photographs

Treat the search for information like a scavenger hunt or like a detective searching for clues to solve a mystery.

You might begin by choosing one person or event related to your family that just a little is known about. Start with what you have and begin asking questions. You may have an old photograph just waiting to take you on a journey to a different time and place:

- Is that your great-grandfather in the photo as a young boy with his family at a train station?

- Who are the other family members with him?

- Where was the photo taken, and when?

- Was the family setting off to travel or had they just arrived from somewhere?

- Was it a special occasion?

One question that is often overlooked:

- Who took the photograph - a professional photographer, a friend, or a family member? In other words, who else was there that day that didn't end up in the photo because they were behind the camera?

Perhaps you have another old photo that was taken in a portrait studio, with family members wearing their best clothes.

- Who is in the picture?

- How do you know? (Did dear old Aunt Helen tell you? Be advised that relatives may mistake identities in old photographs. So who else can you show it to and get a second opinion?)

- Where was the photo taken, and when, and how do you know?

- Is there a studio mark that includes the name of the town?

- Why was it taken - was it a special occasion?

This family connection may spark curiosity more readily - and more deeply - than general photos in a history textbook. It may lead to something as unexpected as an in-depth look at early roads and transportation, and how that influenced where people went to live.

Dig deeper into places and topics

Did you have family in Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit or Chicago in the 1800s? Chances are they traveled there from New York via the Erie Canal - a fascinating study in its own right, and one that will be more meaningful if your children can imagine their ancestors sailing on the mule-drawn canal boats. There are many related topics like this; check out these lesson plans put together by educators for Ancestry:

A great place to research places or topics is the FamilySearch Research Wiki. If you discovered that the family in the photo was departing Massachusetts by train in 1932 to move to New Jersey and live with relatives, you can search on states and cities to learn more about the area your ancestors lived in, and learn what kinds of records still exist for specific places.

Additionally, you might consider that the decision to relocate and live with relatives was caused by the Great Depression, and so you might decide to take time to learn more about that difficult decade. It deepens the understanding when children can make a connection across time; using the real-life experiences of their own relatives offers that connection.

Did you learn that an ancestor committed or was a victim of a crime? If appropriate, center research around the crime and the people involved.

If an ancestor claims to have lived in a haunted house, kids may be interested in researching the property.

Pursuing the intriguing stories is one of the best parts of family history research, so go with whatever sparks interest.

Search for answers using interviews

Once you have enough questions, begin figuring out who to ask and where to search in order to answer them.

If possible, start by asking grandparents or other older relatives using the list of questions and the photograph(s) as prompts. Be sure to write down or record the answers you receive! Maybe your relative can't tell you much about the people/place/event in the photograph but knows of others who might help: a longtime friend, neighbor, or pastor, for example. Take any leads you get, and ask the same questions of each person; this will give you a sense of how accurate the details are.

Lori Coffey, or Trainer Lori as she is known on YouTube, has a wonderful video teaching kids how to interview their relatives that you can watch below.

Genealogy for Kids: Interview Your Relatives by TrainerLori

Talking to other members of the community begins to widen a child's worldview. It shows children how their extended family did not live in isolation but was a part of a community, especially in decades past when transportation was limited and families moved around much less.

With that in mind, consider questions like these:

- Where exactly did your family live in town?

- What kind of work did they do?

- How did they typically get around - by walking, horse or carriage, train or trolley?

- Trolley cars were much more common 60-80 years ago than they are today.

- Look for old photos of your town to see if it had a trolley system.

Research using artifacts, heirlooms, and records

Now that you've got some understanding of a specific family/place/event, it's time to search for more clues that will help to paint a picture and make that family come alive again! Where to begin? As before - always start at home, and homes of relatives.

Look for other photos or albums, a family Bible, an address book or diary, legal papers, or even a recipe box, for you never know what other interesting notes might be tucked away in it. You no doubt looked through family photos and artifacts already, but this time you'll go through them again to see if they shed new light on the subject of your current quest.

What comes next? After scouring the attics and memories of relatives, turn your search to:

- local historical societies

- libraries

- courthouses

- churches

- cemeteries

Online records. Fortunately, most places have websites, so you can do your searching from home. For example, if you find the headstone for great grandpa, you can note the date of death on it and use that to locate a newspaper obituary, which may offer lots of information and more clues to pursue!

Browse the 1950 census records online at Ancestry for free, and some library systems allow home access to their more complete Ancestry Library version. Check with your local library to see what might be available from home. Most states offer virtual libraries, and kids might find interesting records like a military pension record describing how an ancestor was injured during the Civil War.

FamilySearch offers access to millions of records online-including censuses, vital records, family trees, and more-with free registration.

An aside: When using official records, find out why the record was created. Whether it is a census, a military record, a will, an apprenticeship record, or some other type of official record, understanding the legal purpose of the record can give perspective on the included information and even offer research hints. The reasons the records were created will also help kids make connections about their ancestors' place in history.

Write, record, and share your finds

Once you've learned all you can about a family/place/event, what comes next? Depending on the age of your children, find a way to Write, Record, and Share. Older students may write a narrative to attach to the photos and send a copy to relatives. Students of all ages may prefer a hands-on project.

Here are two examples:

Maps. Check out My Maps from Google-it allows you to personalize maps with details related to your ancestors:

- their family homes

- schools

- places of worship

- workplaces

- cemeteries

- distances to other family members

You can add your own details and share them electronically with family. This would make a great geography unit study and provide a finished project to show for it.

Grandma's Attic Trunk. Do you feel wistful that there's no proverbial "trunk in the attic" left behind by an ancestor in your family? Then consider starting one! Begin collecting:

- old family photos from relatives

- newspaper clippings

- postcards

- yearbooks

- awards/trophies

- lockets

- military medals

Make your own little chest or scour antique shops for an old-fashioned trunk to store your extended family's artifacts, and learn how to care for them. Someday, you will be the ancestors your descendants come looking for, so include recent artifacts as well as older ones.

Use these tips for family tree projects

- Traditional pedigree charts list direct ancestors only. It can dead-end quickly and require lots of tedious research. Instead, make a three-generation chart of your extended family: include siblings, stepfamily, aunts-uncles-cousins. Free family group sheets are available from Ancestry.

- Work with just one parent or grandparent's line so as not to confuse all the lines of people and feel overwhelmed when trying to keep them all straight. Alternatively, have one child focus on Grandma Sullivan's family while another learns all about Grandpa Benson's line.

- A simpler approach is to have children start with themselves! Have them chart out a personal timeline of their lives; using those details, they can then write a little autobiography - the story of their own life, and one they can build on over the years. They may then be ready to make a timeline or biography for a parent or grandparent or other older relative. This is easier to do with someone still living whom they can interview and is much less overwhelming than trying to begin with that Civil War ancestor or one who emigrated from Lithuania.

Additional resources

(affiliate links)

Bringing History Home: Local and Family History Projects for Grades K-6 by M. Gail Hickey - Designed for classroom teachers; filled with activities.

Zap The Grandma Gap: Connect with Your Family by Connecting Them to Their Family History by Janet Hovorka - Hovorka has a number of books for children that focus on an event (Pioneer, Civil War), national heritage (British, Swedish, Danish, German), and religious heritage (Jewish, Mormon).

The Kids' Family Tree Book by Caroline Leavitt - Good for younger children, ages 7-11; learn about different ways to build a family tree and do related projects.

The Great Ancestor Hunt: The Fun of Finding Out Who You Are by Lila Perl - Especially useful if you know your ancestors immigrated between 1880-1920. Helps children think about why people immigrated to the US, how they got here, where they settled, what kinds of work they did, and what kinds of recipes and traditions they brought with them.

Growing up in Coal Country by Susan Campbell Bartolleti - Learn what life was like for children in Pennsylvania who worked in the coal mining industry.

Black Potatoes: The Story of the Great Irish Famine, 1845-1850 by Susan Campbell Bartolleti - Black Potatoes depicts the story of the Irish potato famine and its effect on emigration.

All of Bartolleti's books are good for special topics in social history.

Karen Skelton homeschooled her two children through high school and served for many years as a state leader with the Organization of Virginia Homeschoolers. She has taught US history in a homeschooling co-op and is a freelance genealogist. She and her husband, Robert, live in Greensboro, North Carolina, where Robert is pursuing a PhD in US. History. Their children embraced the concept of “the world as their classroom” and are currently exploring new paths in Oregon and Australia – because the learning adventures never end.

Karen Skelton homeschooled her two children through high school and served for many years as a state leader with the Organization of Virginia Homeschoolers. She has taught US history in a homeschooling co-op and is a freelance genealogist. She and her husband, Robert, live in Greensboro, North Carolina, where Robert is pursuing a PhD in US. History. Their children embraced the concept of “the world as their classroom” and are currently exploring new paths in Oregon and Australia – because the learning adventures never end.

Leave a Reply